I was first introduced to the work of Diane di Prima in an undergraduate

Beat literature class. She was not a part of the syllabus ad the only reason

I had discovered her poetry was because I was asigned a project in which I

had the freedom to study any Beat writer of my choice. The class did not cover

any female Beats and I wanted to bring a woman's voice into the Beat literature

conversation. As I worked on the project for the class I noticed two things: One

was that I was the only student to focus on a woman writer. The second was that I

was begining to fall deeply in love with the poetry of Diane di Prima.

The first of di Prima's poems I read was "An Exercise in Love" and the second

poem I read of her's was "Brass Furnace Going Out: Song, After an Abortion". When

I compared the two poems, I saw that one expressed the pleasure of having a body

while the other expressed the pain of having a body. However, both of these poems

also expressed the strength, beauty, and perseverance of women. As I read and

studied more of her work, it became clear to me that di Prima is a women's woman.

She is not afraid to write about the realities of being a woman. She writes about

love, intimacy, beauty, and sensualism all while writing about pain, oppression,

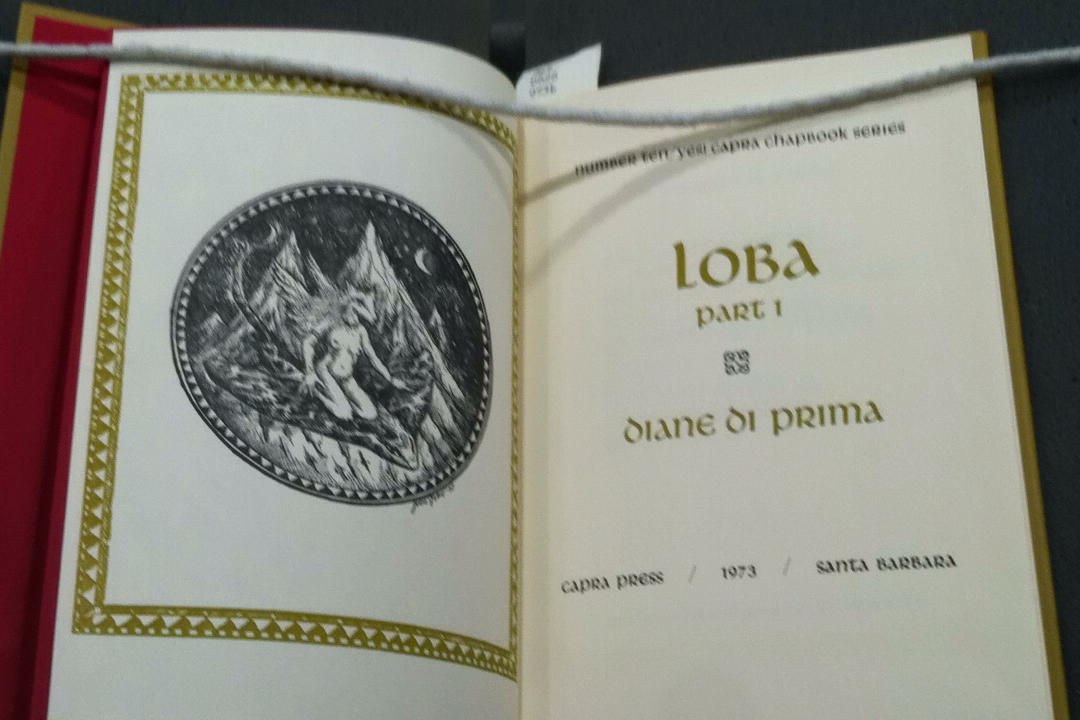

bitterness, and realism. She wrote bravely. When I finally read di Prima's master

work, Loba, I knew that I was reading a very special and important literary piece.

It was an interesting academic venture, but also a deeply personal read.

Reading Loba for the first time was a special moment; the moment became spiritual

and the poem felt like a meditation. Whenever I return to that work, I still feel

as though I am seeking guidance from an ancient, religious text: even though the

first draft of the poem wasn't fully conceived until 1973. Despite her young age of

forty-five, di Prima's great mother wolf goddess easilly could have been guiding

the women of the world for thousads of years. Loba represents the vigin, the mother,

the warrior, the boss-lady, the teacher, the prostitute, the crazy-cat-lady, the

priestess, and the crone. She has no race, age, or sexual preference. Loba is simply

the noble, feminine spirit. The entire poem--whether you read the completed, 300 page

work, or the small and humble pre-first edition publication--is a celebration of

women and the human spirit. It celebrates all women without judgment, which is why

the piece is so important, personal, and powerful.

I go back to Loba more often than most other literary texts. I think about the Loba

when I walk down the street alone. I think about her when I am with my closest female

friends. I think about her when I lead rituals. The Loba comes to me when I need

protection, love, courage, and leadership. She has become sybolic of my own heart, but

also symbolic of how I respect and connect to other women.